The Money Czar

Investigation by Max Katz

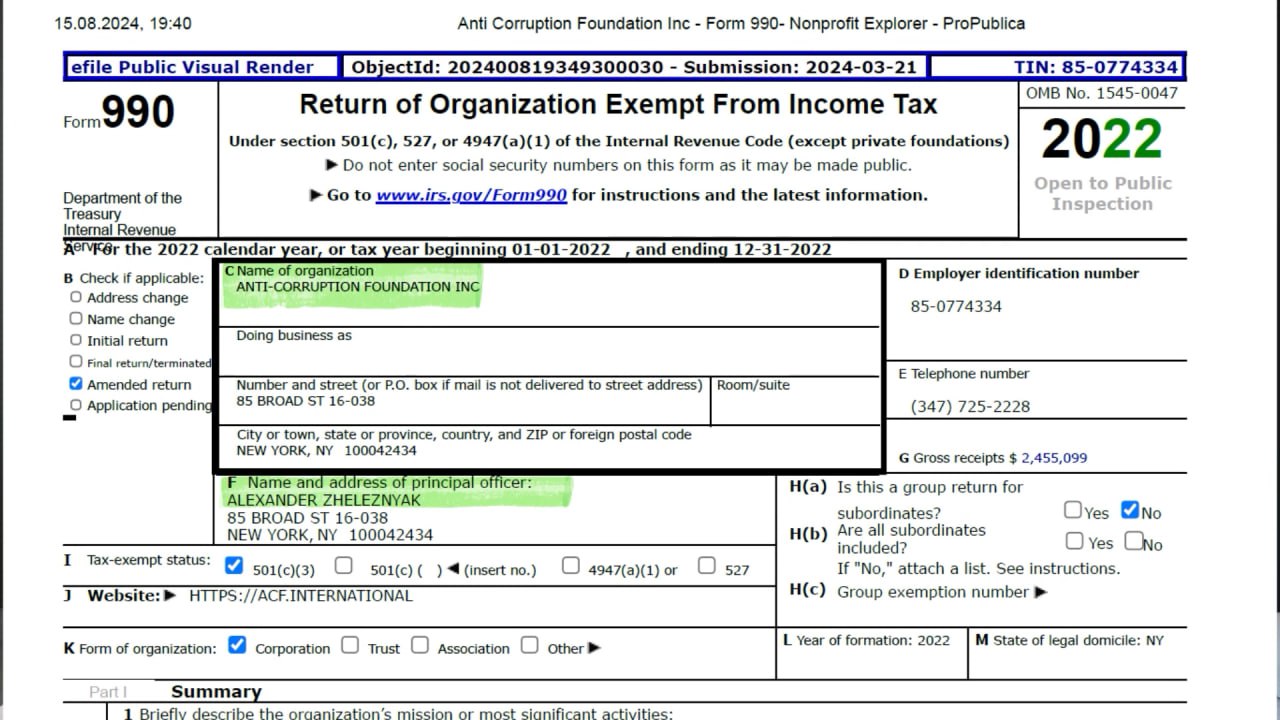

If you are reading this, you must have watched the video of the investigation conducted by our team. It took us three long months to peruse the ins and outs of a brazen fraud perpetrated by bank executives Sergei Leontiev and Alexander Zheleznyak.

Although doing investigations is not exactly in my wheelbase, this case called my attention as it went beyond the simple story of the two bankers, their failed bank operations, and $1 billion in stolen money. Some particular circumstances of this scam felt personal. To dodge the responsibility for their crimes and retain the money, Leontiev and Zheleznyak have been posing as the victims of political persecution in Russia. In this pursuit, they have been aided by a major Russian opposition force: the Anti-Corruption Foundation (ACF).

This website details the unprecedented heist, the banksters’ capture, and the way they have been trying to whitewash their acts by misrepresenting the charges as being politically motivated. It also offers the official records demonstrating that the duo are no political dissidents, but ordinary thieves.

Give it a read.

1. The Beginning

The 2000s and early 2010s was a time when banks were embezzled left, right, and center.

Probusinessbank saw $1B heisted.

The Beginning

The scam perpetrated by the Probusinessbank executives was neither one-of-a-kind nor even the largest ever. The 2000s and 2010s in Russia was a time when huge asset heists and money laundering schemes were being perpetrated on an unprecedented scale.

Schemes almost became a byword for the Russian economy. Using cash for tax evasion purposes was a regular business practice, as was creating shell firms that are essential to a shadow economy. At one point, such outfits accounted for almost 50 percent of a total number of Russian-registered businesses.

In 2012 alone, the official records estimated the amount of money transferred from the Russian economy abroad at $35 billion. At least 75 percent of the bank insolvency cases involved criminal foul play. In other words, it was not just that the banks misinvested their money—their executives were deliberately stealing the assets from the customers.

Some of the felonious schemes were truly mind-boggling. For instance, the Russian Laundromat scheme involved at least 18 Russian banks on top of the Latvian and Moldovan ones. Over the course of four years, the offenders stole, laundered, and withdrew an estimated total of a staggering $20 to $80 billion.

While that was unfolding, the regulator’s capabilities were rather limited. Back in the day, the Russian banks could not turn down a customer’s application for a new account if the required I.D. was in place. For Russian nationals, the only prerequisite was a Russian domestic passport. The banks were not allowed to shut down an account, even if its holder seemed too fishy. Even if the holder proved to be bogus, the bank could not stop servicing the account, and the holder would not face any charges.

Given the above, $1 billion stolen by Leontiev and Zheleznyak was nothing new. That being said, that fraud coming from Probusinessbank was a bit of a shocker. After all, the bank enjoyed a reputation as a decent and even creative outfit. Its customers had access to various perks and were happy with the service quality.

A Business-Friendly Bank

The bank was co-founded by Sergei Leontiev and Alexander Zheleznyak in 1993. In 2003, the co-owners used it as a basis for their LIFE. Financial Group. The idea was to create a holding group of banks with centralized standards, tailored to different kinds of customers.

The Group was developing a regional network. Its corporate values included loyalty to the customers, partnership, and teamwork. Probusinessbank earned a reputation as a financial institution with cutting-edge management tools. Long story short, it was an advanced bank run by open-minded individuals. The co-owners were pushing the boundaries. The customers found the bank reliable, while the bank employees enjoyed the informal executive leadership style.

Probusinessbank was a fairly large bank. Before it got delicensed, it had $200 million worth in net assets.

Probusinessbank also used to be ranked rather highly.

2010

— 9th in asset growth in Q1

— 11th largest consumer bank

2012

— Company of the Year Award in customer-oriented approach

But in 2011, the co-owners changed tack and began hatching an elaborate money heist scheme.

Chapter 1

The Scheme

2. Typical Scheme

We are starting with Embezzlement 101. How do you steal from a bank using foreign shell firms?

If that is something you are well aware of, feel free to skip over.

Typical Scheme

What does the simplest bank fraud scheme look like? The unsupervised owner/executive issues a loan to a company they control. The company goes on to transfer the money to the owner/executive’s personal account and declares its insolvency.

These schemes are well-known to the regulators whose job is to expose or even thwart them. To this end, the banks are required to stick to a set of transparent accounting procedures that will prevent them from stealing the funds.

But the misuse and heists do happen every once in a while as seasoned financial executives come up with new stratagems or overhaul the existing ones to slip away from the regulators’ oversight through a maze of loopholes.

The protagonists of our investigation, the banksters Sergei Leontiev and Alexander Zheleznyak, proved to be creative enough to MacGyver an ingenious scam of their own. Let us zoom in on it.

3. Probusinessbank’s

Signature Scheme

Probusinessbank's ingenious plan: Instead of lending money to a shell firm, you can secure their obligations. The regulator will be clueless, while the scheme will allow you to be embezzling for years without getting caught.

Probusinessbank’s Signature Scheme

4. Vermenda Scheme

Probusinessbank's collateralizes a loan to Vermenda, a foreign shell company, controlled by Zheleznyak and Leontiev. For four long years, Vermenda was taking out the loans without ever bothering to repay them.

A total of over $153M ends up being smuggled using this scheme.

Vermenda Scheme

Legal withdrawal

In 2011, Probusinessbank started placing its funds with the London-headquartered Dinosaur Merchant Bank Ltd. (DMBL), a small financial firm regulated by the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

Probusinessbank opened a checking account and a deposit account with DMBL. In September 2011, Probusinessbank deposited $20 million. The bank would go on to transfer a total of over $243 million to its DMBL brokerage account.

So far, so good. Both companies were within their rights to do what they were doing. A Russian bank may deposit its funds with a foreign brokerage account for extra revenues. That was a common practice.

5. Ambika Scheme

Ambika, another shell company affiliated with Probusinessbank's execs, borrows from the OCIL investment firm, while Probusinessbank collateralizes the deal with securities. Ambika never repays the loans, and Probusinessbank loses another $213M.

Ambika Scheme

Vermenda was not the only foreign shell company used as a pumping station for the Probusinessbank customers’ money.

The bank’s correspondence with Otkritie Capital International Limited (OCIL), a U.K.-based investment firm, shows that Probusinessbank opened four accounts with OCIL and deposited its securities.

On November 29, 2012, OCIL issued a loan to the Cyprus-based Ambika Investments Limited.

Ambika was yet another shell company with an authorized share capital of €8,550, employing just two staff members. The company did not submit any financial reports, and its actual address did not match the registered address. Ambika had no assets or financial activity. Why would OCIL issue a loan to it? You guessed it, Probusinessbank’s securities were used as collateral for its obligations to OCIL.

Just like Vermenda, Ambika was controlled by the Probusinessbank executives. This is evidenced by the transcripts of the Central Bank meeting dated May 21, 2015, and the Trasta Komercbanka briefing we have mentioned while detailing the Vermenda withdrawal scheme.

Starting in November 2012, OCIL was lending money to Ambika. Officially, OCIL was lending the securities to Ambika, while Ambika was borrowing the money from OCIL, with those securities being used as collateral.

Probusinessbank was unconditionally liable to OCIL for Ambika’s fulfillment of its obligations, which was enshrined in the guarantee agreements dated Nov. 29, 2012, Dec. 20, 2012, and Mar. 15, 2013.

Under these agreements, Probusinessbank gave OCIL the title to all of its assets that could serve as collateral for Ambika’s liabilities. OCIL could also sell those assets and pocket the proceeds unless Ambika repaid the debt.

Those assets were not subject to withdrawal so that Ambika’s liabilities could always be secured by that collateral.

Besides, the introduction of temporary administration to Probusinessbank or delicensing would bring about an early termination to the trilateral agreements.

And that is exactly what happened.Russia’s Deposit Insurance Agency (ASV) took over the bank as its temporary administration, and in August 2015, it reached out to OCIL and requested the return of the securities. OCIL declined to recover the assets citing the collateral obligations related to Ambika and Probusinessbank.

The agreements were called off. Ambika was notified of the debt amount. OCIL sold Probusinessbank’s securities and used $213 million to recoup the debt.

- Archive of documents about Ambika

- Letter from Otkritie bank to Probusinessbank

- Cyprus report on Ambika

- Minutes of the meeting at the Central Bank

- Meeting of Trasta Komercbanka (original)

- Meeting of Trasta Komercbanka (in Russian)

- Letter from Otkritie bank to Probusinessbank. Refusal to return assets

- Letter from Otkritie bank to Ambika Letter from Otkritie bank to Probusinessbank. Guarantees of Probusinessbank for Ambikas loans (page 5)

6. Merrianol

Fraud Scheme

The Merrianol fraud scheme is almost identical to the Ambika stratagem. The loans are collateralized by Probusinessbank's securities the bank has borrowed from a brokerage firm.

Merrianol Fraud Scheme

On Mar. 29, 2013, Probusinessbank entered into an agreement with BrokerCreditService (Cyprus) Limited (BCS). The executives registered a new Cyprus-based shell company: Merrianol Investments Limited with an authorized share capital of €2,000 and two staff members employed.

Merrianol was yet another link in Probusinessbank’s money-laundering chain. Merrianol and Vermenda were exchanging large amounts of money, which was detected by Trasta Komercbanka’s Control Division that found the companies’ affiliation.

Merrianol took out a loan from BCS. Probusinessbank offered its funds and securities it had transferred to the BCS accounts as the Merrianol loans collateral.

The Merrianol fraud scheme was almost identical to the Ambika scheme. The loans granted to the shell company were backed by the securities borrowed from the broker.

In a June 2015 letter to Probusinessbank, a BCS employee said the bank could recover its securities by paying the collateral covering Merrianol’s indebtedness.

On Aug. 10 and 11, 2015, after the temporary administration took over the bank, BCS took around $105 million in Probusinessbank’s assets to cover the debt.

By the time the CB revoked Probusinessbank’s license and appointed the ASV to take charge of the bank, the bank’s accounts had at least $470 million missing. Although the financial reports covered that amount, the money was withdrawn from the bank using the Vermenda, Ambika, and Merrianol embezzlement pathways.

But it did not stop there. There were many more such schemes in play.

7. Immoger

Fraud

Scheme

In an even ballsier move, Probusinessbank grants a loan to Zheleznyak-owned Immoger, secured by two guarantors. One week later, Zheleznyak terminates the agreement, rendering the loan unsecured. It never gets repaid. Probusinessbank is down €4M.

Immoger Fraud Scheme

As Probusinessbank was nearing an ignominious demise in 2015, the owners could no longer be bothered to engage in a convoluted financial chicanery. Instead, they literally began lining their own pockets without restraint. Even though the amounts transferred got smaller, they no longer attempted to launder the money or otherwise sugarcoat the heist.

In Germany, Dmitry Zakharov, a Probusinessbank employee, set up Prim Holding GmbH. We have a copy of the informational letter proving the company was custom-founded for Alexander Zheleznyak.

Prim Holding, in turn, owned a subsidiary shell company: Immoger Group GmbH.

On Mar. 15, 2015, Probusinessbank entered into a loan agreement with Immoger. But sure enough, the bank could not grant a loan to that shell outfit without any collateral to secure it. Otherwise, the transaction would have been flagged by the bank’s internal control. Hence the two supplementary agreements naming two individuals as the loan guarantors.

On Mar. 24, Immoger received a €4M loan, which was immediately rerouted to Prim Holding, the Zheleznyak-controlled company.

According to the official records available, merely a week after the transfer, Probusinessbank terminated the collateral agreements, and so, the repayment was no longer guaranteed. Importantly, the termination papers were signed by Zheleznyak as the bank’s chairman of the board. Perhaps none of his underlings dared to take the risk.

Thus, the guarantor loan turned into an unsecured loan issued to Zheleznyak’s company. Simply put, the bank’s money somersaulted straight into his pockets.

Needless to say, Immoger never repaid the loan. On Aug. 7, 2015, the day the temporary administration stepped up, Prim Holding began transferring the funds to the accounts of other companies formally owned by Dmitry Zakharov.

- Information letter

- D&B report on Immoger

- Shareholder agreement of Immoger

- Loan to Immoger

- Immoger account statement

- Transfer to Prim Holding GmbH

- Registration of Dmitry Zakharov's company

- Money transfer from Zakharov's company Loan agreement between Immoger and ProbusinessbankTermination of agreements between Immoger and ProbusinessbankOpening of a credit line for Immoger at Probusinessbank

8. Notes

Non-Payable

Zheleznyak and Leontiev decide to entertain a side gig by having “special category” customers pay a ton of cash for the promissory notes signed by the Cyprus-based shell firms. One of the note holders is the daughter of a top Prosecutor-General's Office honcho. Once the bankers fled Russia, the repayment was cold-turkeyed.

Notes Non-Payable

As Leontiev and Zheleznyak fled Russia, their bank’s crippled balance sheet did not just take a toll on Probusinessbank’s customers. Another category of scammed individual that took a direct hit were the note holders. We are not going to take a deep dive into it, but here is what happened.

Importantly, this story is fundamentally different from the previous ones. Using these shell company schemes, they defrauded the banks customers of their money. Those were ordinary people and business owners who kept their money with a large bank without ever expecting any foul play. As for the notes payable, this scheme only applied to the «special category customers», some of them controversial characters.

But Leontiev's attorneys seek to conflate the two plotlines as if those were identically. They were not.

Zheleznyak and Leontiev had a special category of customers in search of unconventional financial strategies. Those individuals had a ton of cash but no proof of origin to enter a financial market. In exchange for that cash, LIFE Group’s executives were offering them notes payable at a 10% annual interest rate.

A note payable is a type of security also referred to as a promissory note.

Those “special customers” were duped into investing truckloads of cash in exchange for those promissory notes. Crucially, those notes were not signed by the bank’s executives but by the Cyprus-based shell outfits or LIFE Group, a regular company with an authorized share capital of just 10K rubles.

Those sketchy types were swapping their cash for a scrap of colored paper secured by the promises coming from Leontiev and Zheleznyak. Sure enough, they were never reimbursed once the banksters beat a hasty retreat.

Who were those mysterious customers? Two of them, Alexander Varshavsky and Kamo Avagumyan, the co-owners of the Avilon car dealership, pressed charges in the U.S. Except that effort drew a blank. They found it hard to prove the elusive bankers owed them dozens of millions of bucks by producing a crummy note payable signed by a shonky Cyprus-based outfit.

Avagumyan and Varshavsky presented the court with a bulk of evidence proving the embezzlement on the part of Probusinessbank’s execs. These records are now publicly available. Some of those documents ignited our investigation.

Another note holder was Diana Karapetyan. Between April and June 2015, she paid a total of $4 million in exchange for the notes payable from another Cyprus-base shell company: Venom Trading Limited.

We had no clue who that woman was. But as irony would have it, back then, there was a top-ranking Prosecutor-General’s Office honcho named Saak Karapetyan. Incidentally, he had a daughter named—surprise, surprise—Diana.

So, bear in mind Probusinessbank’s execs were very much part of the establishment and in cahoots with the ruling class. Prosecutorial bigwigs would have never entrusted an outsider with a multi-million-dollar fortune. We will get back to it in our future discussion of Leontiev and Zheleznyak posing as the opposition figures.

Chapter 2

Exposed

9. Exposed

Probusinessbank's shady dealings raise the alarm bells with international credit rating agencies and the Central Bank, Russia's regulatory authority. Once the schemes get exposed, the Central Bank revokes the bank's license. The customers lose their money, while the bankers take flight to evade prosecution.

Exposed

Tell us if there’s something we need to know

Leontiev: It’s no big deal

Lomov: It’s no big deal

CB: Update your balance sheet

Delicensed

Temporary administration bumps into new heist proofs

Bank’s creditors losing their money

On-the-run bankers re-emerge as political dissidents

Russian Arbitration Courts’ Decisions

Chapter 3

Where's the Money

10. Money

Laundering

Here we explain the basics of money laundering and the whole point of these schemes.

Money Laundering

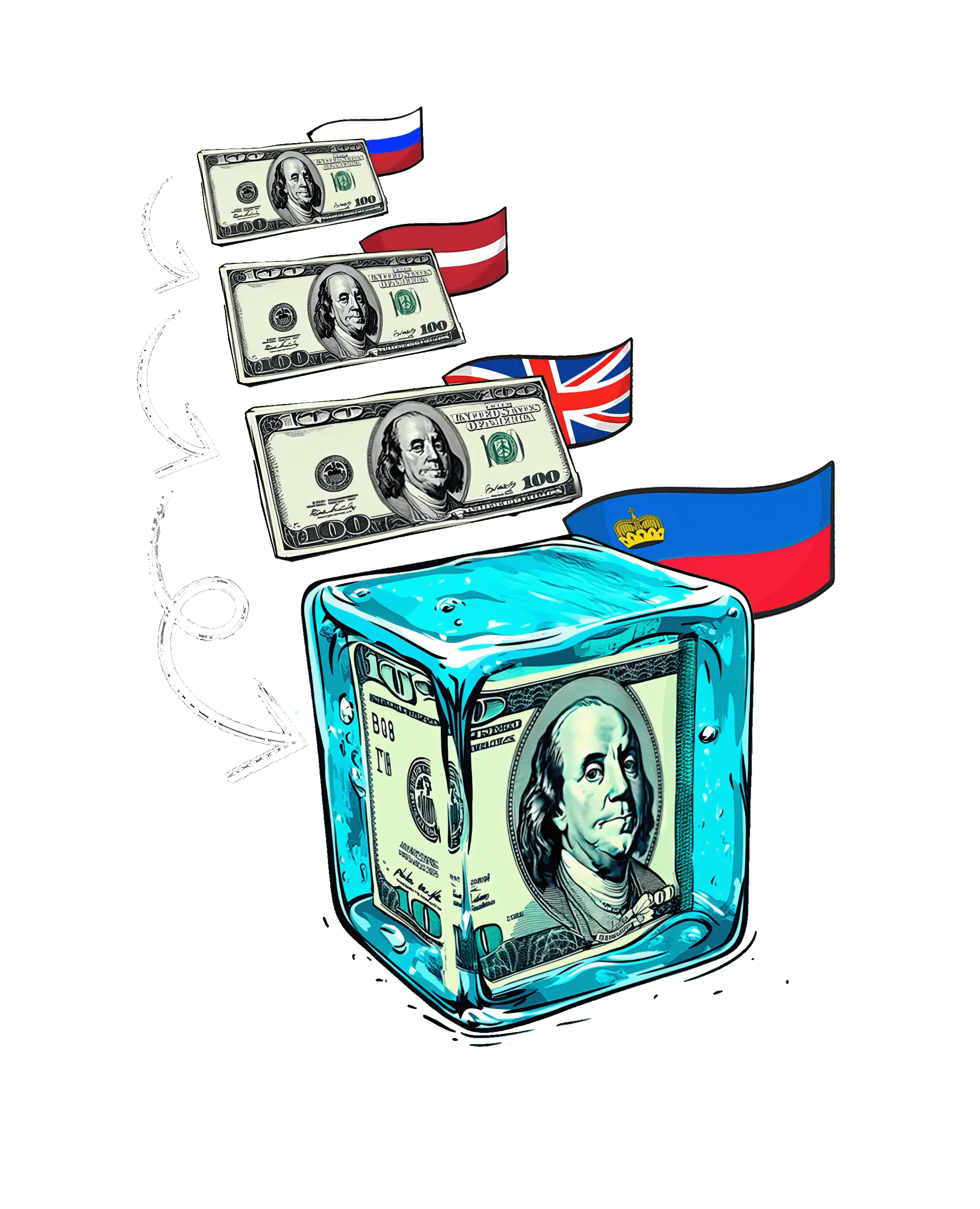

Follow the money, or so they say. How about tracking down the twisted journey of the scammed Probusinessbank funds? How is using them and are they by any chance recoverable? But before we can dive into it, here is a bit of theory for you.

Money laundering stands for a set of transactions intended to muddy the real origin of the funds and eventually “legalize” them. Money laundering is broken down into three stages: placement, layering, and integration.

First, you need to place your dirty money with a bank. Whether you pulled off a shady loan scheme, a grocery store heist, or a lucrative dope deal, you need to find a bank that will eagerly snag your cash and open an account for you—or maybe even accept a troubled loan.

But finding such banks is a tall order. After all, a million bucks stuffed into a duffel bag and powdered with a white substance may raise some red flags with the bankers. There are not exactly a lot of banks willing to credit dozens, if not hundreds, of millions of bucks to the newly minted account of a customer with no registered office address and a company size of two employees. Well-established banks normally want no part in the money-laundering machinations. So, you need to find the one that will turn a blind eye to any inconsistencies with either the customer or their money.

Once you have found the bank and credited the money, you start layering it. After all, crediting the money alone will not safeguard the deposited amount. The next audit will have it flagged as “suspicious”. What you want to do straight away is initiate a string of transactions that will result in having your money mixed up. You can transfer the money back and forth between companies and accounts, take out random loans, repay them, pay for the services, etc.

These transactions are all economically pointless. This money buys you nothing and covers nothing of any financial value. Instead, a ton of money is being ceaselessly and relentlessly reshuffled in a way that is ultimately misleading to the authorities so that it all seems to be well-earned in good faith.

At this stage, the embezzlers tend to stay out of transferring any amount of money to their accounts directly, which could eventually help link the laundered funds back to the original tainted money. It is this stage that features most slip-ups as the fraudsters may be tempted to nibble away at the shiny pie.

Myriad transactions later, the origin of the funds can be considered well-camouflaged and barely traceable. That is where the integration part kicks in as the embezzlers start transferring the money from the fishy shell firm accounts to well-reputed banks.

Regardless of where your money comes from, money-laundering is a serious felony. Whatever the motivation to draw a veil over it, shuffling the money back and forth between the shell companies to muddy its origin is an illegal stunt.

Money laundering directly affects the individuals whose money was stolen. But it also tangentially hurts the financial system, undermines people’s trust in the banking system, and chips away at taxpayer money, should the government have to make up for the losses. Hence the harsh sentences the advanced justice systems are slapping the launderers with.

11. Detailed

Transactions

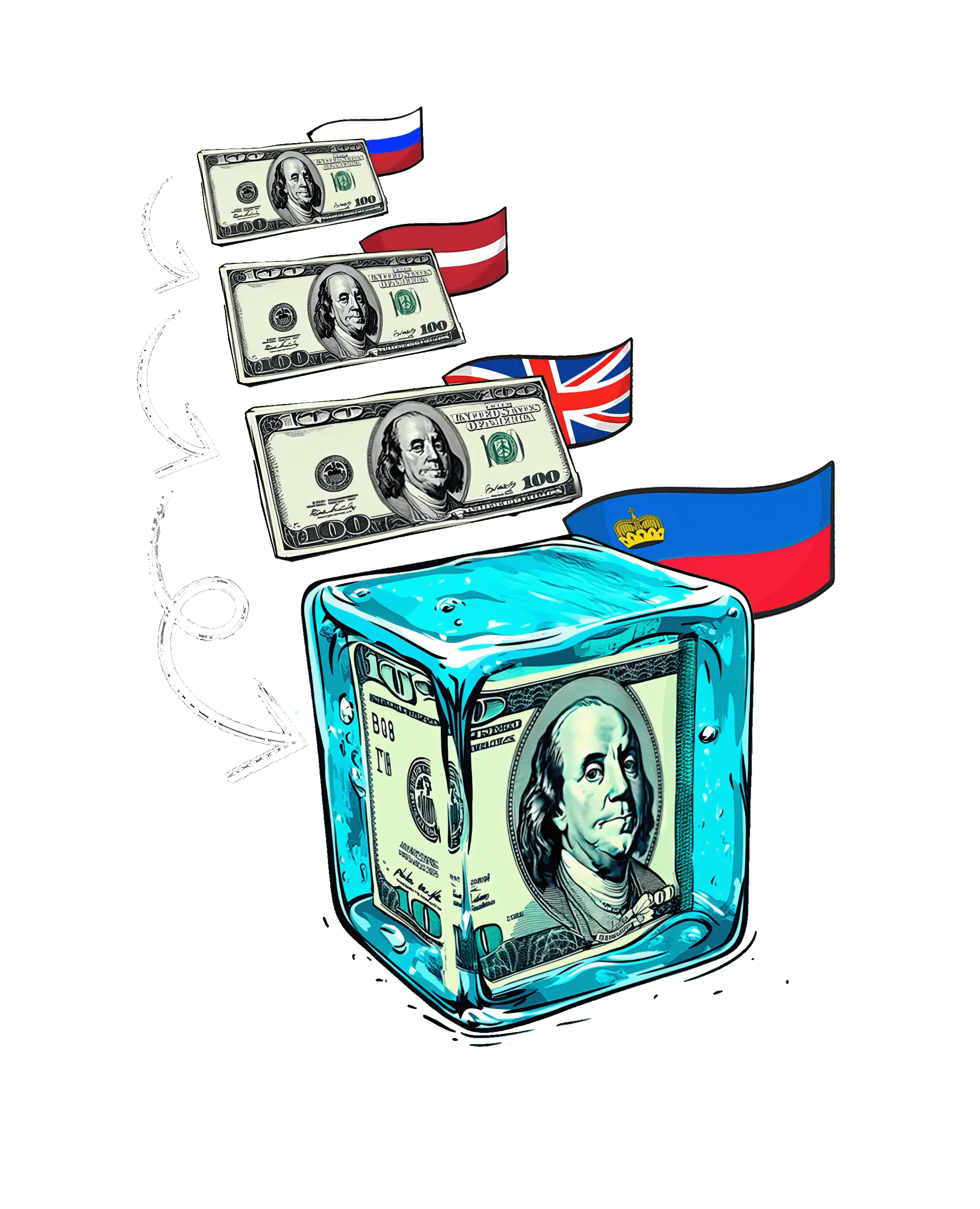

The banksters seek to launder the stolen assets. The funds first land in Latvian bank accounts and start traveling back and forth between various shell company accounts. Their final destination of the laundering journey is the Wonderworks company's account with London-based Morgan Stanley. The money then gets transferred to Liechtenstein where the local authorities seize the funds.

Detailed Transactions

With the theory out of the way, let us now follow the Probusinessbank money’s further moves once the sham loan scheme was done and dusted. Vermenda’s case is the best documented one.

The publicly available information about the accounts and companies implicated in that massive fraud is limited. But the official records we do have access are enough to paint the overall picture of the embezzlement patterns and for us to figure out the final destination those funds have reached.

After DMBL granted the loan to Vermenda, it should have been placed with a bank. To do so, they needed to find a bank unscrupulous enough to open an account for them to credit dozens followed by millions of dollars to, without the bank management batting as much as an eyelid.

A decent will inquire about the source and the legality of the customer’s income as well as the economic endgame of the intended transactions. Vermenda is a shell company with no assets or financial activity. Their endgame is to steal the Probusinessbank customers’ money. It goes without saying the account itself, as well as the transactions, may raise a few eyebrows. Not everyone’s, though.

Back in the day, some Latvian banks, including Trasta Komercbanka and Baltikums Bank , were offering a literally one-of-a-kind deal by letting anyone contribute their money, whatever the origin, to their system. Probusinessbank’s fraudsters were not by far their only dubious customers. Said banks were implicated in a number of other massive scams, including the Russian Laundromat scheme. So, these Latvian banks were not particularly inquisitive or principled, for that matter.

Vermenda opened a few accounts with those banks, and that is where the DMBL loans ended up.

Then came the second stage of the money-laundering procedures. To muddy the waters and conceal the assets’ origin, Vermenda engaged in countless transactions involving over a dozen foreign shell firms, such as Greenex, Finbay, Vesvora, Izatelom, Lankora, Larienta Management, Digitime, and others. We got access to the detailed transactions for these companies’ bank accounts, which enabled us to identify the final beneficiaries and piece together the journey the stolen funds had taken on.

Among Vermenda’s multiple transactions we have access to, none are indicative of it conducting normal business operations. No office space rent, no payroll, no internet bills—none of the usual stuff. Instead, they were shuffling back and forth billions of dollars, and those transactions involved the other shell companies present in the money-laundering scheme.

But some payments really stand out and are of particular interest.

For instance, in February 2014, Vermenda used its Latvian account to send three tranches for a total of around €2 million to the Anti-Corruption Foundation’s (ACF) current CFO, Alexander Zheleznyak. That happened long before the bank got delicensed. Think about it: part of the stolen money was transferred to the bank’s chairman for personal use.

On top of the $153 million embezzled through the DMBL fraud scheme, the Trasta Komercbanka accounts alone processed a total of almost $2 billion in “Vermenda’s money.” Vermenda also drew the money transfers from LIFE Group’s other subsidiary companies. These were all documented.

A series of Byzantine transactions eventually led to the bank accounts of Wonderworks, which was demonstrably owned by Sergei Leontiev. That was found by the Liechtenstein court that ended up seizing the funds.

Besides the Trasta Komercbanka money-laundering account, Leontiev somehow managed to open an account with the top-drawer Morgan Stanley bank in London on behalf of Wonderworks. That account was conceived as the final destination for the already laundered and legalized scam money. In December 2015, more than $105 million was sent from Morgan Stanley to Wonderworks’ Liechtenstein accounts.

On May 17, 2017, the Princely Court of Vaduz seized Leontiev and his companies’ funds. Liechtenstein’s Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) had found compelling evidence proving that it was the money stolen from Probusinessbank and then laundered.

So, it went beyond the theft. Money laundering is a prosecutable felony that, if proven, would land the banksters in a prison bunk. To avoid this miserable fate, they had to start laundering their reputations, too.

The bankers seem to be down on their luck.

The hot war is still years away, and international financial intelligence agencies are cooperating with their Russian counterparts. The scammed money is about to get recovered and returned to its rightful owners. Besides, the fraudsters themselves are facing the odds of being extradited to Russia.

That is where the duo has another brainwave. What if they start posing as political exiles and government critics persecuted by the Putin regime?

Chapter 4

Political Aspect

12. Reputation

Laundering

Just like the money, reputations can be laundered, too, it turns out. Both Leontiev and Zheleznyak rushed to have their transgressions erased. Here are the nuts and bolts of scrubbing a felon's history clean as explained by Leontiev's attorney in his sit-down with a Free Russia-funded podcast.

Reputation Laundering

Now that the money-laundering part is clear, let us see what the embezzlers were doing to scrub their tarnished reputations clean, and that is where the fraud saga took a stunning plot twist.

Just to be clear, Leontiev and Zheleznyak did not embark on a reputation-laundering journey because they suddenly got filled with remorse for the crimes they had committed and sought to start with a clean slate. Of course, not. It was about the money and their own safety.

Indeed, making enemies seems to be part and parcel of someone pilfering one billion bucks. There are the victims of the scam naturally seeking justice and reimbursement. Then there are the foreign financial intelligence agencies busting their chops to build an airtight court case. The fraudsters are in for quite a ride. Here they have their accounts frozen. Others want them to be extradited. And they can never discount the odds of being prosecuted for money laundering in a Western country.

But once you have conjured up a reputation as a victim of an autocratic rule and convinced everyone that the embezzlement charges are politically motivated, you get a shot at having your assets back and winning an extradition court case. Therefore, investing in your suddenly revamped reputations can pay off big time.

But invoking politics was not exactly Leontiev’s or Zheleznyak’s brainchild. The two had notable predecessors.

In 2011, Andrei Borodin, the former president of Bank of Moscow, fled Russia and applied for political asylum in the U.K. At the time, the bank came under scrutiny over using a shell firm to withdraw over $400 million.

Sergei Pugachev, Mezhprombank’s beneficiary, also insisted he was being persecuted as a political dissenter. As a result, his name got struck off Interpol’s wanted list, even though in 2010, the official inquiry uncovered a $2B gap in Mezhprombank’s finances.

How were the devious banksters supposed to cook up a credible theory proving their political affiliations, seeing as they had none?

The most popular methods include cooperating with famous organizations or non-profits, doing charity work, and mingling with well-respected public figures.

The banksters decided to go for the ACF affiliations. They took part in the foundation’s events, snapped pictures of them alongside the famous members, donated the money, and even infiltrated the company’s management structure. The ACF employees were penning letters of support and publicly pledged their trust in the bankers’ reputation. They could not have asked for more, right?

The second tactic is doctoring the media coverage. Ordering a couple of puff pieces, making sure the smear mentions are limited to a bare minimum, and hiring seasoned public relations wizards with great command of the local media landscape.

The Reich Way

In October 2021, an American lawyer named Jonathan Reich made an appearance on Free Russia’s Foreign Office podcast. The host and the attorney discussed how Russia “manipulates the anti-money laundering systems.”

Now, what makes Mr. Reich and the podcast episode he appeared on worthy of a separate chapter? The thing is, Jonathan Reich hails himself as a provider of “creative legal strategies.” Besides, he represents Sergei Leontiev. Credit where credit is due: the strategy he came up with for Leontiev was creative indeed. Under it, his client is posing as an exiled political dissident targeted by the Russian regime.

But back to the podcast. The episode in question features Mr. Reich breaking down Leontiev and Zheleznyak’s criminal defense strategy leveraging the motif of honest entrepreneurs being politically persecuted. Go ahead and give it a listen or read the episode’s transcript.

Throughout the episode, the host and the guest discussed if Russian authorities could at all be trusted when it came to financial crime. After all, Russia is an autocracy and a kleptocracy that cannot be taken seriously. Reich doubts that European financial intelligence agencies should seize any assets in countries like Switzerland solely based on the Russian oversight agency’s claims that those were stolen from Russia.

Besides, he goes on to question the integrity of Western financial intelligence units investigating Russian entrepreneurs and their money because these institutions may, too, be bribed by the Putin regime.

Reich then argues that any money withdrawn from the Russian banks should be, by default, considered clean without even bothering to look into the evidence offered by the Russian side. In addition, he basically says there is essentially nothing wrong with money laundering. According to him, it is merely the movement of assets. After all, honest money can, too, be shoved back and forth to hide the origin of these funds.

But again, like we said in the chapter on money laundering, an attempt to hide the funds’ origin is considered a felony regardless of the origin’s “cleanliness”.

Nonetheless Reich’s musings clarifies the logic that underlies Leontiev and Zheleznyak’s whole criminal defense strategy. That very logic spawned the political aspect narrative with regards to Probusinessbank’s fraud allegations.

What is the upside to this narrative? If swallowed by the foreign courts, it will lead them to drop the charges without trying the case on the merits. They will refuse to look into the official records or interrogate the witnesses in a bid to find out if the money has indeed been stolen and needs to be returned to its rightful owners. The political argument will outweigh it all and help the fraudsters keep the money and remain free.

But it takes more than just fleeing abroad and declaring yourselves political exiles and regime critics for the persecuted bankers narrative to get off the ground. The courts are not exactly known for their disarming credulity, and this excuse may prove a tough sell. It is further exacerbated by the evidence pointing to Probusinessbank’s scheming.

Importantly, these events were unfolding in the mid-to-late 2010s when Russia was not yet a pariah state. Russia’s law enforcement was still fruitfully cooperating with their foreign counterparts in the anti-money laundering department. The bankers needed solid proof of their story. In July 2017, the duo got a lucky break.

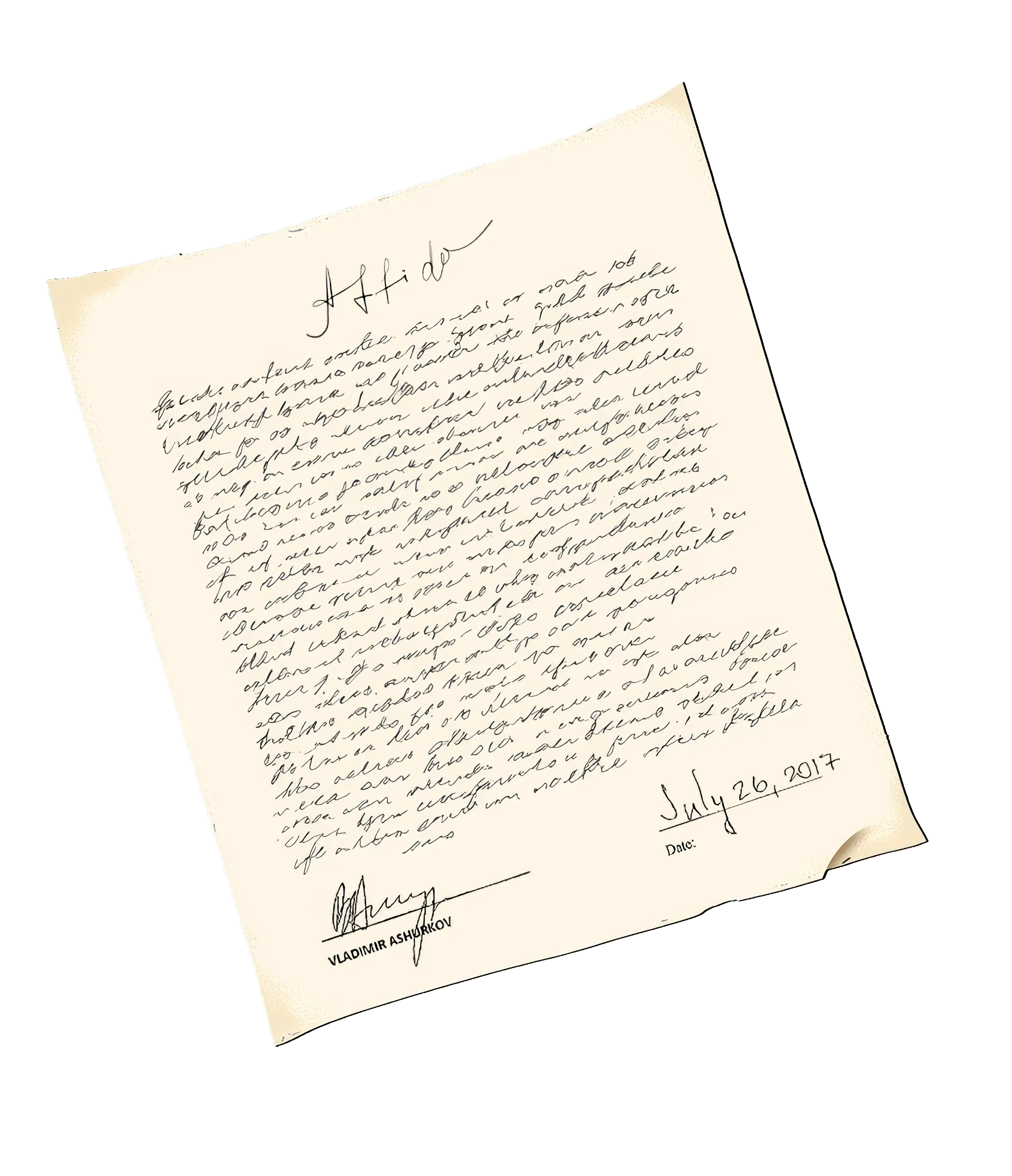

13. Vladimir Ashurkov’s

Affidavit

Two months after the funds were seized by the Liechtenstein authorities, Vladimir Ashurkov travels to the U.S and submits a statement. In his statement, he hypothesizes that the charges brought against the bankers may be trumped-up, while Probusinessbank may have been deliberately bankrupted by the Russian regime. That was all allegedly due to Leontiev's and Zheleznyak's dissenting views and his willingness to support Alexei Navalny.

Vladimir Ashurkov’s Affidavit

In late May 2017, the Liechtenstein authorities froze the accounts of the three companies run by Leontiev on the money laundering allegations tying it all in with Probusinessbank.

On Jul. 26, 2017, two months after Leontiev’s accounts were frozen in Liechtenstein, Vladimir Ashurkov, the then-ACF’s executive director, traveled to the U.S. to submit a statement. His statement would then solidify the banker’s legal and political defense strategy in Europe. For example, the Polish court cited the statement as it declined to extradite Yaroslav Alekseyev, Probusinessbank’s former vice-president.

Ashurkov’s statement tells the story of Alexei Navalny and the repression he and Ashurkov himself were subjected to. He goes on to bring up the 2012 plan to issue the Navalny card together with Bank24.ru. This project will be described below.

Although the statement does not explicitly claim it, the implication is that Bank.24 was forced to cease operations following that episode. “This outcome was a setback to Mr. Navalny's Anti-Corruption Foundation but was not surprising given the Putin Administration's history of stifling the political opposition, including the illegal seizure of banks and business assets

'<...>'

It is very possible that the arrests, false charges and the seizure of the banking group which happened in respect of LIFE, its executives, and its members was a result of their attempt to help Alexei Navalny and Anti-Corruption Foundation in its absolutely legal civil work.”

The statement shrugs off the charges brought against Zheleznyak and Leontiev as trumped-up and politically motivated. We now know they were not trumped-up. Later, we will explain why they were not politically motivated, either. But for now, bear in mind that Ashurkov’s statement was used as a major piece of evidence portraying Leontiev and Zheleznyak as political exiles.

ACF dismisses the document as being an actual affidavit since it wasn't offered under oath. However, neither Ashurkov nor ACF dispute the statement itself substantively.

14. Bankers do

volunteer work

and donate

to ACF

The banksters come up with a political persecution cover story. They are doing their utmost to fit the bill of being true opposition figures as they take part in political rallies, donate to ACF, and even join the foundation's top brass.

Bankers do volunteer work and donate to ACF

The bankers began to extensively donate to, and work with, ACF.

Leonid Volkov told Financial Times that starting in 2021, Leontiev had been donating $20,000 a month, or $240,000 a year, to ACF. He may have been donating before 2021, but this data was not revealed. Currently, ACF is not reporting these donations.

Besides, Zheleznyak, Probusinessbank’s former chairman of the board, founded ACF’s U.S. branch. He was and still is the organization’s CFO. ACF has various titles registered across the U.S. But public records see him mentioned as either vice-president or CFO or principal officer.

Here is an example of Zheleznyak signing the important documents on behalf Anti-Corruption Foundation Inc. On behalf of the foundation's New York branch, Zheleznyak authorized the incorporation of ACF's affiliate into the Virginia jurisdiction.

ACF’s public support of the bankers makes the political persecution narrative a compelling case both for the courts and for the public opinion.

15. Political

persecution narrative

blows up

The fraudsters are lobbying members of the U.S. Congress in a bid to pressure Liechtenstein's ambassador to the U.S. into having the Liechtenstein court overturn its ruling. It kickstarts a flurry of pro-Leontiev puff pieces in the German-language media.

Political persecution narrative blows up

Lobbying efforts in Congress

The political persecution narrative could be boosted by the support from top-tier politicians, preferably the U.S. policymakers. That is why in 2016, Sergei Leontiev began his lobbying efforts with various U.S. institutions.

In the U.S., all lobbying activities are reflected in public records listing both the areas of interests and the stakeholders’ names. Everyone can access a government website and find the information on the lobbyists, their interests, and the agencies or government structures they are working with.

We have gleaned the publicly available information on Sergei Leontiev’s lobbying campaign. In 2016, he registered as a lobbyist and reached out to the Department of State with an eye to the banking system and international relations. In 2017, he promoted his agenda with the Department of Justice and the DoS. In 2018, he lobbied the DoS and the FBI.

In 2018, he re-registered as Grid Market Research, a firm that keeps lobbying the U.S. agencies to this day.

Grid Market Research had a prominent role in this story. At least once, in October 2015, it received a payment from the Latvian account owned by Wonderworks, the stolen money receptacle. In 2021, Grid Market Research was listed as one of ACF’s top donors. It also shares the company address with Anti-Corruption Foundation USA.

Upon registering as a lobbyist, Grid Market Research has invested a ton of money to carry on with Leontiev’s lobbying endeavors. Both Leontiev and his company have spent a total of more than $2.5 million lobbying the agencies.

What does a typical lobbying scheme look like? One example we know of is that Grid Market Research donated to the Atlantic Council, a famous U.S. think tank. According to the organization’s 2018 report, the donation amount was between $50,000 and $100,000.

In 2018, the Atlantic Council ran an expertly report on the way Russia was “interfering” with the U.S. judiciary. The piece cited Alexander Zheleznyak and Sergei Leontiev as the alleged victims of the unlawful bank seizure. The article claimed that the innocent duo was being targeted by a lawyer whose name was on the Magnitsky list, which is true in that the ASV had hired an attorney sanctioned by the U.S. under the Magnitsky Act. However, the bankers were being targeted for the real crime they had committed.

We cannot definitively say if Leontiev and Zheleznyak’s attempts to lobby the members of the U.S. Congress panned out. Nevertheless, in July 2020, three U.S. representatives wrote letters to Liechtenstein’s ambassador to the U.S., looking to have the Princely Court reconsider its account freeze orders.

These letters claim Leontiev was stripped of his business because of his support for the Russian political opposition and his commitment to the anti-corruption cause. As proof, they cite the Magnitsky case, which had nothing to do with Probusinessbank, and the Polish court ruling based on Ashurkov’s statement.

On May 16, 2022, two U.S. representatives published a letter to President Joe Biden. The letter tried to bring his attention to the Deposit Insurance Agency (DIA, ASV) because it led the “Kremlin-directed efforts to nationalize the assets of targeted Russian financial institutions, funneling the assets of privately owned businesses to now-sanctioned Russian state banks such as Sberbank, VTB and Gazprombank.”

According to the high-profile letter-writers, many of those businesses (closed banks) were owned by “shareholders and entrepreneurs who lack sufficient political protection from these kinds of schemes or have been blacklisted as political targets of the Russian state.”

The letter called on the ASV to be sanctioned to counter the ASV legal team’s attempts to recover the assets. According to the congressional representatives, it would help curb financial aid that bankrolled the war effort and, lo and behold, “protect the assets of Russia’s private financial institutions.”

Importantly, the ASV has never boasted a spotless reputation. This is a corrupt agency that takes advantage of the insider information to blackmail and leverage thievish bankers and hires the unscrupulous lawyers mentioned in the Magnitsky list.

But in this case, the pushback against the ASV had nothing to do with malpractice or its ties to Russia’s autocratic political regime. Far from it, they were attempting to undermine the ASV’s crusade to reimburse the scammed Probusinessbank customers.

This initiative worked, and the ASV ended up sanctioned. The banksters must have breathed a sigh of relief.

German-language media campaign

On May 18, 2017, the Liechtenstein authorities froze the accounts owned by Sergei Leontiev and his companies, alleging the money had been embezzled from Probusinessbank. The court decision spurred a flurry of pro-Leontiev publications in the German-language media. They hailed him as a political exile and “Navalny’s banker” and compared his persecution with that of Magnitsky, Khodorkovsky, and Navalny himself.

On Dec. 5, 2020, Liechtenstein’s largest daily newspaper ran an interview with Leontiev’s attorney. According to the lawyer, the Russian justice system was targeting the dissident banker because of the Navalny card project the way it had formerly cracked down on Khodorkovsky and Magnitsky.

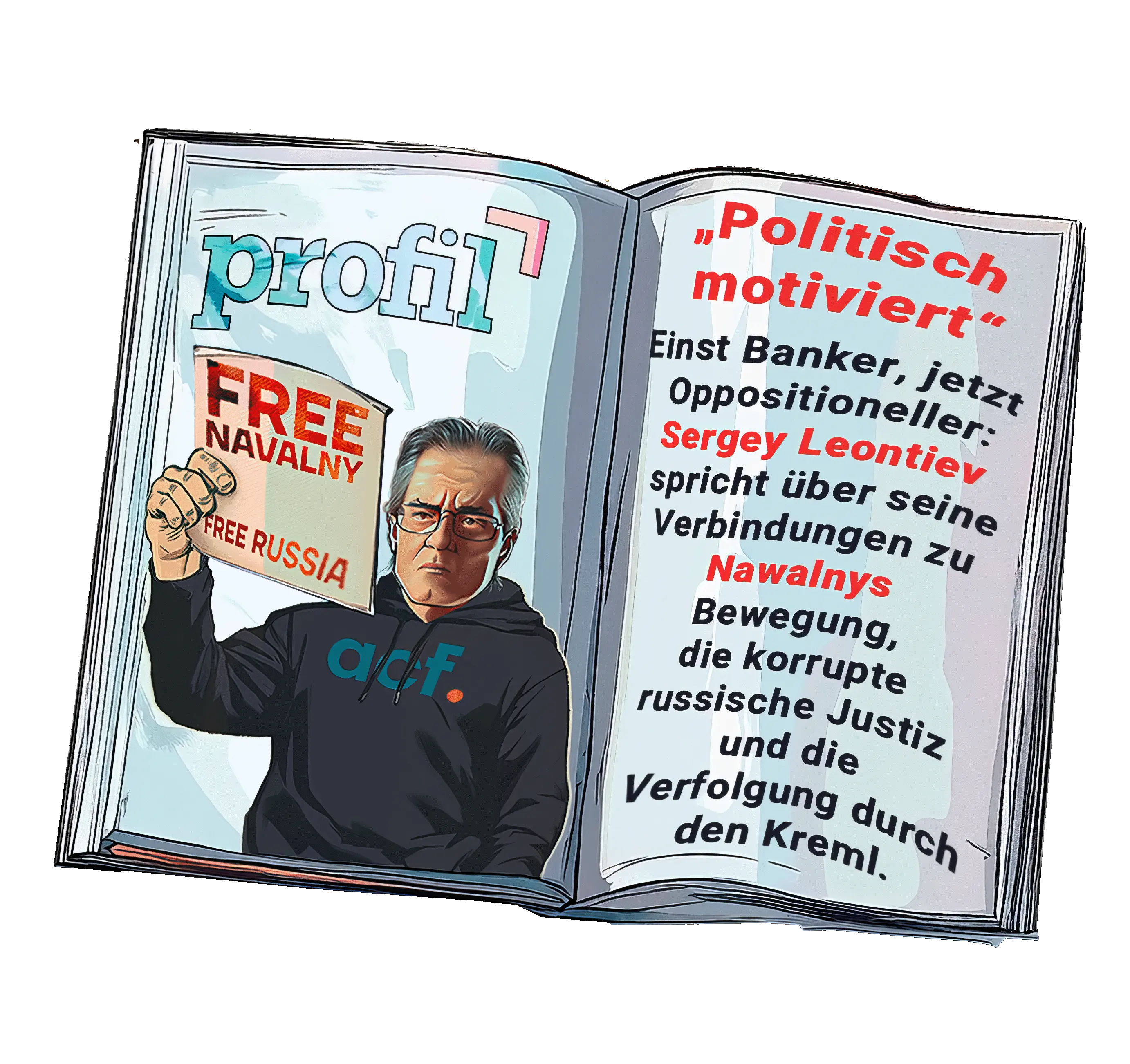

In 2022, the Austrian-based profil.at penned three articles on the subject, including an interview with Leontiev. He was repeatedly referred to as a government critic, a dissident, and “Navalny’s banker.”

In November 2020, Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (SRF, Switzerland) ran a story on Probusinessbank, Sergei Leontiev, and, you guessed it, the Navalny card project. According to SRF, the Russian government pressed charges against Probusinessbank because of their collab with ACF. But the outlet never mentioned the stolen money or the fraud scheme.

And that is by far the most obnoxious aspect of the story. Sergei Magnitsky exposed a government corruption scheme and subsequently died in pretrial detention. Alexei Navalny was the biggest government critic for years and ended up assassinated in a prison colony. Mikhail Khodorkovsky lost his Yukos company and spent ten years behind the bars. It takes a particular brand of cynicism to invoke these cases for the defense of those fraudsters.

And it was not about extraditing the duo to Russia. It was intended to help the banksters brush off the claims of the defrauded customers who tracked down their stolen money and sought to recover it.

Support from public intellectuals

What else could “corroborate” the political persecution cover story? One way would be producing an expert assessment by someone with intimate knowledge of Russia. In January 2018, Sergei Leontiev hired Professor Anders Åslund, an economist specializing in Eastern Europe and Russia, in particular. In the early 1990s, he served as Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar’s advisor. He was well-versed in Russia’s economic landscape and authored several academic papers on the Russian economy. Besides, he has always been a staunch critic of the Putin regime.

On Jan. 12, 2018, he testified in the U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York, where he offered an overview of “the political and economic state of affairs in Russia” in the context of Probusinessbank’s closure.

Basically, he just outlined the basic facts about the current Russian system: no rule of law, poorly protected property rights, the government’s obsession with the preservation of power and personal enrichment.

Both the judiciary and the prosecutor-general’s office are totally corrupt. The government stripping entrepreneurs of their businesses is a common practice. He illustrated his claims with the Khodorkovsky and Magnitsky cases. The Central Bank, he continued, is corrupt, too. Some of the banks were deliberately bankrupted to take over the assets. The delicensing and shutdown of Probusinessbank, he concluded, was just one of those cases.

Fair enough. On the one hand, the Russian system is indeed utterly corrupt and cannot be trusted. It can plunder a private bank or jail a businessperson that has gotten in their way. It seems that Western courts should be particularly discerning and be treating the charges on a case-by-case basis to tell a politically motivated case from the actual embezzlement cases.

However, the only caveat was that Professor Åslund was arguing against deciding the case on the merits just because it happened in Russia and there was no point in chasing that rabbit hole.

16. Ashurkov’s

statement skews

Polish court

ruling

In 2019, Ashurkov's statement convinced the Polish court to refuse to extradite Yaroslav Alekseyev, Probusinessbank's senior executive, on a Russian warrant. The court motivated its ruling by suggesting it might be a case of political persecution on the part of the Russian government.

Ashurkov’s statement skews Polish court ruling

In February 2019, the Polish authorities arrested Yaroslav Alekseyev , the vice-president for corporate finance at Probusinessbank, in the Probusinessbank embezzlement case.

Alekseyev could be extradited, and that is when he applied for political asylum. At first, he claimed he was a Jehovah’s Witness, a denomination that had just been outlawed by the Russian government. However, during the trial, his defense strategy revolved around him being politically persecuted by the Russian regime over his dissenting views.

That claim was supported by the statement Ashurkov had signed while in the U.S. The court ruled against the extradition, the Polish prosecutors challenged the ruling, but then the court of appeals literally quoted Ashurkov’s statement:

“<...> the evidence presented in the criminal proceedings against Mr. Yaroslav Alekseyev raise considerable suspicions. The evidence suggests that the criminal charges may be politically motivated

<...>

The Probusinessbank employees’ alleged cooperation with Alexei Navalny, one of Russia’s major opposition politicians, has a profound effect on the ongoing litigation, for there is reason to believe that the charges brought against Mr. Yaroslav Alekseyev may be part of a repression campaign seeking to terminate said cooperation.”

That is how the political persecution claims were officially mentioned by a European court, which further boosted the political persecution cover story.

17. Liechtenstein

court ruling

In 2022, the Liechtenstein court dropped the charges against Sergei Leontiev. The court predicated its ruling on the Polish court's decision and concluded that Leontiev was wanted on politically motivated charges. To this day, the banksters have been successful playing the part of political dissents, which prevent the court cases from being tried on the merits.

Liechtenstein court ruling

Let us get back to the Liechtenstein part of the money saga. On May 17, 2017, the Liechtenstein prsecutors office launched a probe into Leontiev's money-laundering case. On May 18, the $116 million transferred from Morgan Stanley were seized.

In March 2022, the Liechtenstein authorities eventually dropped the charges against Leontiev. On Apr. 28, 2022, the court declined to pursue new charges.

The investigation failed to trace the funds' true origin and dropped the case citing a political aspect thereof. The account freeze was apparently lifted.

But how come? What did they do to make the court reconsider and subsequently refuse to return the smuggled funds to their rightful owners?

The answer is simple. They found the right words suggested by a shrewd attorney. The Liechtenstein court that was considering the reimbursement of the bank’s creditors cited two reasons for calling off the litigation. One was that the charges were allegedly politically motivated. Secondly, the ASV was a sanctioned state-run corporation representing an unfriendly country that could not act as a plaintiff in the Princely Court of Vaduz.

So, the court dismissed the case as politically motivated, referencing the ruling of the Polish court that had allegedly made an evidence-based decision.

Meanwhile, the Polish court that handled the extradition case chose its words carefully. According to the Polish judiciary, the case “might” have been politically driven, for it “might” have targeted the bank’s bankruptcy and its subsequent acquisition by the government.

Besides, according to the court records, the bulk of evidence, including witness testimony and Vladimir Ashurkov’s statement arguing for the bankers’ ties to Navalny, stoked reasonable doubt as to the criminal charges brought against Yaroslav Alekseyev. Ashurkov’s statement is, in fact, even quoted in the resolution.

But the Liechtenstein court could push further, try the case on the merits, and peruse the official records obtained outside of Russia’s jurisdiction. Moreover, it was related to the money laundered via Wonderworks that wound up frozen in Leontiev and his companies’ Liechtenstein accounts. Sadly, the Liechtenstein court decided against pressing on. Instead, it just referenced the Polish court ruling.

According to the Princely Court of Vaduz, based on the Polish court filings, “the Russian criminal prosecution targeting Mr. Yaroslav Alekseyev and the second plaintiff <...> is politically motivated.” Odd that. The Polish court did not state it. It only invoked reasonable doubt.

Based on that conclusion, the preliminary probe the Liechtenstein prosecutors had conducted for several years was dismissed without ever being decided on the merits. The creditors’ appeal seeking to resume the litigation was dismissed, too.

Ashurkov’s statement played a major role in both litigations. The statement convinced the Polish court there might have been a political aspect to it, and stopped it from getting to the bottom of Alekseyev’s dealings. The Liechtenstein court then merely referenced the Polish court decision and discontinued the preliminary investigation.

There is an ongoing trial in Liechtenstein that already features the bank’s customers trying to recover their seized funds. Vladimir Ashurkov will be tried as a witness. Most likely, he will be insisting the case is politically motivated.

Meanwhile, the litigation is ongoing in Liechtenstein. The banks's customers—this time, without the ASV's mediation—are trying to recover their money from Leontiev. The latest decision in one of these trials, the one that came in May 2024, appointed the witnesses to be tried. Leontiev insisted that they reach out to Vladimir Ashurkov who could explain «the real state of affairs.» The court granted Leontiev's request. It will give Ashurkov the floor for a two-hour witness deposition.

(Because it is an ongoing trial, the lawyers advised that we withhold the information unrelated to Ashurkov's statement.)

It has been nine years since Probusinessbank was declared bankrupt.

The on-the-run banksters, Zheleznyak and Leontiev, used the stolen fortune to bankroll their bogus cover story about their political dissent.

Chapter 5

Anything

but politics

18. Navalny card

Let us rewind it a few years back. In 2012, ACF conceived a promising project, a bank card their supporters could use, with 1% of the cashback credited to the foundation. The project never got off the ground as no bank agreed to issue such cards. Both Probusinessbank and Bank24.ru co-owned by Leontiev and Zheleznyak snubbed the offer, too.

Navalny card

Let us dig deeper into the banksters’ boisterous explanation. According to Ashurkov’s statement, at the root of the government’s bitter enmity toward the duo was their support of ACF and willingness to issue the Navalny card.

What was it all about?

In 2012, ACF conceived a project of a custom-designed bank card. One percent of the card-holder’s total expenses would be credited to the foundation as a cash-back option paid for by the bank. The issuer was also expected to benefit from the collab by advertising its name, reaching new audiences, and boosting its profits.

On May 15, 2012, ACF announced the new project. The card could be pre-ordered from Navalny’s website. But ACF’s partner bank was never mentioned.

The project would never get off the ground. The bank’s name, like we said, was never revealed. But on May 15, 2012, the day the card was announced, GQ ran an article citing an unnamed source.

According to the magazine piece, the bank tapped to launch the card was part of LIFE Group.

Outside of this shaky “inside scoop,” there is nothing to suggest the Navalny card project had anything to do with Probusinessbank, LIFE, Leontiev, or Zheleznyak.

The article says that Anton Shubenkin, Probusinessbank’s senior spokesperson, denied the rumors. Even GQ’s source that claimed the bank had agreed to launch the Navalny card added that “some of the Group’s co-owners know almost nothing about the project.”

19. Political Dissidence Theory

After the schemes were exposed and part of the stolen money was seized in Liechtenstein, Leontiev and Zheleznyak decided to misrepresent the criminal charges and Probusinessbank's bankruptcy as being politically motivated. The reason for that persecution? Ostensibly the Navalny card they had nothing to do with whatsoever.

Political Dissidence Theory

The 2012 would-be project was actively used by Leontiev and Zheleznyak when their asset fraud schemes were exposed and they had to flee Russia.

That is how the myth of Leontiev and Zheleznyak being big fans of the Navalny card project first emerged. However, according to them, they had to scrap the plan as the Russian government and the Central Bank officials began putting pressure on them and issuing threats.

After that, they allegedly had to face the music. The presidential office ostensibly decided to punish the honest opposition-minded bankers, while the Prosecutor-General’s Office was itching to dip into their wealth. As a result, Bank24.ru was unlawfully accused of money laundering, delicensed, and closed.

To be fair, the closure indeed looked suspicious. Typically, this fate befell the failing banks that had lost their customers’ money and gone bankrupt. Bank24.ru was, by contrast, financially robust. As the bank was shut down, all of its financial obligations were fulfilled. The Central Bank had no issue with its financial status or balance sheet. It cited the bank’s failure to comply with the internal control standards. Importantly, the bank was involved in the shadow economic processes, including suspicious transactions and the unaccounted-for cash flow.

You can decide if the Central Bank’s allegations were true by comparing the two interviews Leontiev gave to the media.

Sergei Leontiev, secretmag.ru, April 2015

In April 2015, Sergei Leontiev admitted Bank24.ru’s executives had made a mistake that had led to the bank’s closure. According to him, the leadership underestimated the risks, and customer compliance was being handled by the ordinary managers. He vowed to be keeping a watchful eye on the procedures and earn the regulatory authority’s trust.

That is what he said in an interview with secretmag.ru. Neither the interview nor the interviewee brought up the Navalny card or the bank’s support of ACF as a possible reason for the revocation of the bank’s license. Neither the card project nor ACF were ever mentioned. Instead, Leontiev was quick to admit the bank had slipped up, the regulator was within its right to do what they had done, however harsh the decision itself. He promised to improve the bank’s practices.

Sergei Leontiev, Profil.at, January 2022

However, in his January 2022 interview, Leontiev said right out of the gate that they had wanted to back ACF in 2012 by issuing the Navalny card. They were keeping it under wraps, but someone broke the news to the media. That is when the unnamed government officials and Central Bank officials began calling him, insisting that he ditch the idea. Otherwise, the bank would get delicensed. So, they had to pull the plug on the whole project.

Then an unnamed top prosecutor allegedly suggested that the banker sell 50% of Bank24.ru’s shares. The bankers turned down the offer. Later, Elvira Nabiullina said the bank was suspected of money laundering, and that was that for their bank.

In 2015, Leontiev owned up to the customer compliance issues. But in 2022, he decried the allegations as preposterous. Yet, there is no proof of this latest claim.

Implicating Probusinessbank

According to the bankers, the Russian regime and its aides did not stop at that. Some bad guys from the Prosecutor-General’s Office and the Kremlin purportedly aspired to take over LIFE’s biggest asset, Probusinessbank, and demanded that they sell half of their shares.

Needless to say, the “honest opposition-minded bankers” maintain they refused to sell their shares. That is when, according to them, Probusinessbank’s license was revoked under the pretext of liquidity issues. Which was a flagrant lie, if the bankers are to be believed.

The support of ACF cost them their financial group, they claim. The top executives, the “honest bankers” who backed the opposition, had to flee Russia and apply for political asylum elsewhere to dodge the Russian government’s vendetta.

But this is all a bunch of low-grade baloney.

20. Leontiev & Zheleznyak had no role in the Navalny card project

Leontiev and Zheleznyak refused to help Navalny and ACF get the card launched. Moreover, they shrugged off their alleged involvement the very day the rumor swirled.

Leontiev & Zheleznyak had no role in the Navalny card project

On May 15, 2012, ACF announced the Navalny card project, and GQ published an “inside scoop” on LIFE Group’s bank being behind the collab. That is how the dissenting bankers legend was born.

But even the GQ piece admitted Probusinessbank’s senior spokesperson had shrugged it off. According to the magazine’s source, the bank co-owners were clueless about it. But then the article got updated on that same day. Slava Solodky, LIFE’s vice-president for advertising and public relations, retracted the story. He wrote, “We have nothing to do with this project—and never did.”

On that very day, Alexander Zheleznyak, too, said the bank had nothing to do with the project. His statement was not published until later. Perhaps the employees somehow entertained the idea, but the chairman of the board knew nothing about it.

Panteleev’s statement

The fact that Bank24.ru had nothing to do with the Navalny card project was corroborated by Eduard Pantellev, the former chairman of the board at Bank24.ru and member of the board at Probusinessbank. He said:

“The idea of launching a co-branded card with part of a commission fee donated to the Anti-Corruption Foundation was not conceived by Sergei Leontiev. I personally repudiated the idea as it did not align with the bank’s strategy. We found it unacceptable to endorse any political activism as it ran against the best interests of the bank’s customers and shareholders, that is, the bank’s profitability. In my opinion, politics should be kept out of the business processes.”

Panteleev testified in Prague. Now he is based out of London and stays involved with the banking projects. When testifying, he was safe and could not be browbeaten into this statement by the repressive Russian regime.

He asserts that the bank declined to launch the card project not because it was pressured into it by Russia’s intelligence agencies.

Given the above, it is safe to assume the two banksters had nothing to do with Navalny. If there is anyone who can be referred to as “Navalny’s banker,” it is Mikhail Fridman. Navalny opened an account with Fridman’s Alfa-Bank in 2012. That account was used to raise the funds for his mayoral and presidential campaigns. By contrast, Yandex.Money closed the opposition platform’s accounts for their campaigns. The Alfa-Bank account was alive and kicking until 2020. Neither the bank nor its owner was affected by the collaboration.

Or take Alexander Lebedev and his National Reserve Bank (NRBank), for example. Unlike Probusinessbank, they were publicly speculating about launching the Navalny card for several months. They didn’t, in the end. Besides, Lebedev owns a stake at Novaya Gazeta. Moreover, remarkably, back in the day when he was a minority shareholder at Aeroflot, he appointed Alexei Navalny to the board of directors. During his stint with the airline, Navalny was looking into potential corruption schemes and chronicled it on social media.

That is what it means for a banker to have a political stance. Lebedev’s bank ended up getting eviscerated. But somehow it didn’t have an outstanding debt to its customers and depositors. Do you know why? Lebedev was not stealing money from his customers. Here’s what Lebedev had to say.

21. Leontiev & Zheleznyak were getting along well with the regulator

Today, the banksters maintain that the Deposit Insurance Agency, the Central Bank, and the Prosecutor-General's Office all targeted their business and themselves. In reality, though, there is compelling evidence that shows both Zheleznyak and Leontiev as well as their structures were cooperating with the prosecutors and the regulatory authority. They even got the government contracts to help with the resolution of the other bank, which was an immensely lucrative gig.

Leontiev & Zheleznyak were getting along well with the regulator

Other than the banksters’ own statements, nothing corroborates the theory that the Central Bank and the Prosecutor-General’s Office were involved in an illegal Probusinessbank takeover. But we can compare it against the events that unfolded back in the day. What we will find out, though, is that Probusinessbank and its co-owners were getting along quite well with the supervisory agencies.

We have already mentioned the promissory notes the bankers issued to a woman whose name was a full match to that of the deputy prosecutor-general’s daughter. Leontiev and Zheleznyak must have been part of the in-group. Otherwise, no one would have entrusted them with their money with literally zero assurance of repayment.

But there is an even more compelling illustration of their closeness to the Central Bank. Before the fraud schemes got exposed, Probusinessbank enjoyed a spotless reputation. One year before they were delicensed, their bank was tasked with rehabilitating the Solidarnost bank, based out of Samara, Russia.

This is an important point.

What is exactly bank resolution/rehabilitation? Suppose there is a failing bank with lots of bad assets that is facing bankruptcy. The Central Bank must decide whether they revoke its license or try and salvage it.

Bank resolution or rehabilitation is precisely an attempt to salvage the bank. A crumbling bank is taken over by a well-reputed bank.

In 2014, Solidarnost was about to get rehabilitated by Probusinessbank. In April 2014, Vedomosti interviewed Zheleznyak on the subject. He admitted that he would prefer acquiring a new bank through the resolution procedure over purchasing them.

According to Zheleznyak, the rehabilitation of Solidarnost helped him gain more than 500,000 new individual customers and 10,000 corporate clients. Besides, he got a well-reputed bank with professionally trained staff, a regional branch network, and a set of ready-made banking products. On top of that, Probusinessbank was rewarded by the Central Bank and the ASV for taking care of Solidarnost’s failing assets. The agencies offered him low-interest rate loans and, therefore, high returns. Simply put, he got hold of much more money.

It turns out the bank resolution/rehabilitation can be rather lucrative. But what are the eligibility criteria?

The bank in charge of the resolution is picked by the Central Bank and the ASV. The exact procedure is largely a mystery. Oleg Tinkov claims one can only bribe their way into snatching the pick.

And this fact does not mesh well with the theory that the Central Bank, the ASV, the Prosecutor-General’s Office, and the presidential office, above all, considered the bankers as the regime’s worst enemies and settled the score with them by seizing their property. Clearly, the Central Bank had been eagerly cooperating with Leontiev, Zheleznyak, and their companies before they found out those guys had been stealing from their customers.

Oleg Tinkov about banks rehabilitations (1:36:46)22. Leontiev & Zheleznyak were never part of the opposition

Neither Leontiev nor Zheleznyak have ever opposed the regime. Before fleeing Russia, they had never been critical of the government. Zheleznyak sat on the State Duma expert committee. In 2014, Putin awarded him with a medal. The bankers were a loyal part of the establishment.

Leontiev & Zheleznyak were never part of the opposition

So, the bankers had nothing to do with the Navalny card project while reaping the Central Bank-offered opportunities to build their own business through rehabilitating the other banks.

But what if, outside of their professional domain, Leontiev and Zheleznyak were hardcore government critics? What if the Internet is awash with photos showing them holding up the Putin-bashing posters? What if they had been donating to ACF and other protest organizations before their bank’s 2015 collapse? Were they going against the grain and taking huge political risks?

The short answer is: they were not.

Zheleznyak the Medal-Holder

Before fleeing Russia, Leontiev and Zheleznyak were part of the establishment, in fact, so much so that in January 2014, Alexander Zheleznyak was decorated with a prestigious government award (Merit to the Fatherland, 2nd Class).

It is hard to picture the presidential plotting a vendetta on someone they have just showered with accolades.

Zheleznyak awarded a medalZheleznyak sits on the State Duma’s corruption control committee

In July 2014, he joined the expert council of the State Duma Committee on Security and Corruption Control led by the notorious hardliner, MP Irina Yarovaya. That role was at odds with being a defiant pro-Navalny opposition activist.

2014 was the year when supporting the opposition became a high-risk undertaking. Crimea had already been annexed. Navalny had been sentenced in the Kirovles embezzlement case and was under house arrest over the Yves Rocher fraud charges. It was impossible to picture a major bank executive receiving government honors and sitting on a State Duma committee while supporting Navalny. Zheleznyak ticked both of those boxes. It means the system viewed him as one of their own.

23. Kira Yarmysh: Leontiev has never funded ACF (2019)

In 2019, Kira Yarmysh, Navalny's spokesperson, told RBC that Leontiev and his structures had not been funding ACF.

Kira Yarmysh: Leontiev has never funded ACF (2019)

On Feb. 28, 2019, in the wake of Probusinessbank’s Yaroslav Alekseyev being arrested in Poland, Kira Yarmysh, Navalny’s spokesperson, spoke with RBC.

“In 2012, ACF was negotiating with the bank’s managers on the launch of a card where the cash-back proceeds would have been credited to ACF. The bank then snubbed the project. Neither Leontiev nor his companies have ever bankrolled the foundation or our investigations.”

According to Yarmysh, the card deal was not being discussed with the bank’s top executives, and the talks drew a blank. And any past cooperation with ACF was flatly denied.

That card project story is totally unsubstantiated. The bank’s marketing team briefly entertained the idea, but discarded it altogether. The executives disapproved of the project, and it was scrapped. They did not sign a single document or make a single announcement. Everybody literally said that was a trifle story.

And there was no vendetta, either. The government had no reason to be vindictive toward the two bankers, as both Leontiev and Zheleznyak were embedded into the ruling class and treated accordingly: expert committee roles, government honors, etc.

Years later, the bankers and their aides whipped up the card project frenzy out of thin air.

Above the Law: Big Money & Political Clout

There will be no afterword. Instead, we are offering you a set of useful guidelines on telling a politically motivated case from one that is not. The Russian justice system is now awash with politically driven cases, and the Russian judiciary cannot be trusted at all. But it is not to say that anyone convicted by a Russian court is innocent. Political persecution is different from other trials in a number of ways.

The biggest prerequisite is the defendant taking a stand against the system, being vocal in their criticisms of the government, or undertaking something that is at odds with the current ideology or the senior government officials’ worldview. Alexei Navalny would be one such example. He was a prominent leader of the Russian opposition. The economic charges brought against him had a political undercurrent to them. Another example was Sergei Magnitsky who exposed the government’s embezzlement scheme that implicated top-tier officials. That prompted them to slap him with the tax evasion charges.

But that cannot be said of the banksters in question. As for their political stance, no one had ever heard from them before they left Russia. The publicly available information, meanwhile, suggests they were totally in cahoots with the establishment.

The second attribute of a politically motivated case is the government’s overreaction like searching the suspect’s home and office without looking for evidence or conducting an unauthorized search. Team Navalny members were often searched, even though the case did not call for such measures. Sergei Magnitsky was placed in pretrial detention where he subsequently died, even though doing it was almost unheard-of for the economic-related charges.

Leontiev and Zheleznyak were never searched. Their bank was never scoured for any evidence. No one was ever arrested or put in pretrial detention. No one prevented them from leaving the country.

Thirdly, they may pass a new bill shortly before targeting their victim. For example, the 2022 war censorship laws cracked down on the war opponents. Nothing like that happened to Leontiev or Zheleznyak.

The fourth indicator of a political case is the law enforcement and judiciary’s refusal to abide by the current legislation. For instance, a judge may dismiss the defense team’s account or ignore it. As the government began dismantling the International Memorial human rights non-profit, it overlooked the injunction to authorize an official “liquidation protocol.” Instead, the justice ministry just delisted the Memorial as a non-existing organization shortly after the court issued its ruling.

Number five is loose or straight-up illegal interpretations of the unlawful norms. Those included the cases with extremism or terrorism charges against schoolkids playing video games or undergrads discussing politics on Telegram.

Finally, the sixth indicator of a political case is an egregious mismatch between the charges and the sentences. Right now, we are witnessing shockingly long prison sentences being slapped on individuals who, even by the government’s exaggerated standards, have not done anything to “deserve” the lengthy incarceration.

None of these principles apply to the Probusinessbank case or the Russian arbitration court ruling.

When revoking the bank’s license, the Central Bank complied with the legal procedures to a tee. The regulator spent quite a while trying to talk sense to the bank’s executives and politely argue that the sham assets had led to a massive liquidity gap.

The arbitration bankruptcy is now following a standard procedure. There may only be minor infractions on the part of the judiciary, but nothing too outrageous. The creditors are challenging these infractions, and higher courts are overturning those negative rulings.

The arbitration court resolutions are based on the evidence we have shown you.

Significantly, Probusinessbank’s former execs have yet to appeal the insolvency resolution.

There is no evidence to suggest the former bosses ever challenged the delicensing and the interim takeover. To do so, they did not even need to attend court hearings. The arbitration could have reviewed the ruling if they had submitted the appeal records, which they did not.

By way of recap, Leontiev and Zheleznyak are no government critics or political exiles. Before fleeing Russia, they were an integral part of the establishment, both formally and informally. They even held government jobs and received accolades from that government.

Leontiev and Zheleznyak bankrupted their own bank. The funds ended up with the shell companies they controlled. The bank’s customers were robbed of all of their money and now find themselves locked in a years-long litigation. The Central Bank exposed the fraud schemes, issued a warning, deliberated over the findings, and eventually revoked the bank’s license. The investigation into the embezzlement schemes led to the criminal charges brought against the co-owners. The sham transactions were canceled. There was no political aspect to that case. It was a massive crime and nothing else.

The stolen money was used to hire high-profile government lobbyists and expensive lawyers who came up with a legal defense strategy based on a false claim of the case being politically motivated. Those statements misled the foreign courts. As a result, the embezzlers were never found guilty or sentenced. They are enjoying life and thriving off the looted funds.

To top it all off, Russia’s largest political opposition structure is campaigning to let them off the hook. We will leave it at that.